Explaining German history as an aid to genealogy

Where do your ancestors fit?

________________________________________

By John Peel – Life Preserver

Many of our relatives arrived from “Germany” before it was actually a country. For a long time I struggled to understand the history of Germany as a political entity – when and how did it come to exist? Why was there an England, France, etc., for centuries before there was a Germany?

This basic question comes up quite often when doing genealogical research about your “German” ancestors, and it would be nice to have a simple answer. Well, sorry, but there isn’t one. But it helps to get an idea of how the country developed politically, and to put your ancestors in those time frames.

U.S. Census sheets from the 1800s often show “Bavaria,” or “Prussia” for place of birth. Maybe you’ll encounter the less common “Wurttemberg” or “Saxony.” Where are these places? Why aren’t they referred to as “Germany”? Is Prussia part of Russia?

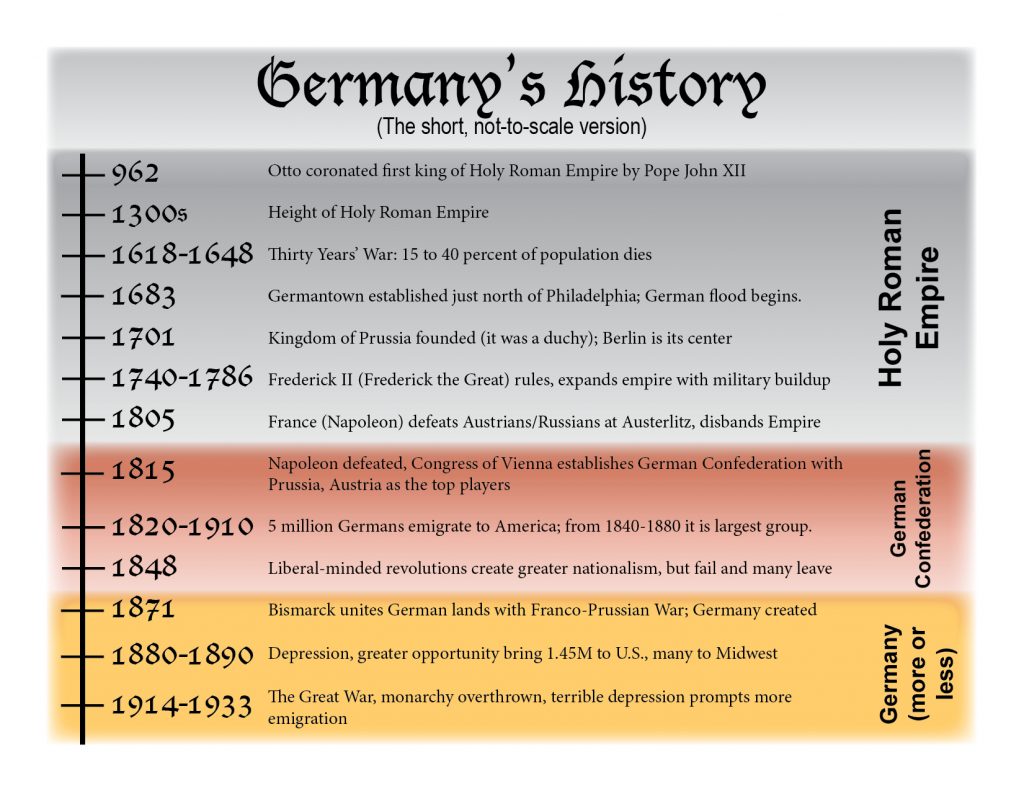

Here’s a brief history of Germany, related as much as possible to American emigration. I’ll just start off by saying the country as we know it didn’t really exist until 1871, following the Franco-Prussian War (a grand time for the victorious Prussians and their ringleader, Bismarck). When the term “German” is used here, at least until we get to 1871, it basically means “German-speaking people living in what we now consider to be Germany.”

Up to 962

A very brief and barely useful synopsis of the first millennium: Tribes inhabited the region now known as Germany. These tribes, sometimes called Teutonic, coalesced into kingdoms, and many accepted Christianity – quite a few of them because the powerful ruler Charlemagne (748-814) made it painful and even deadly for them not to. Settlements were small, and would stay that way for centuries.

In perhaps the most important development of the late part of the first millennium, these folks got better at making beer, learning that hops really helped the flavor. Bavarian hops were discovered to be particularly tasty. German monasteries began brewing beer for mass consumption around this time. But we’ve digressed.

Holy Roman Empire (962-1806)

The first real union of “Germanic” people occurred in this era. As the name implies, the empire had close ties with Italy and the Catholic Church. The pope coronated the Holy Roman Empire’s king. But the empire’s rather loose center was in Germany, and a guy named Otto was coronated king of the Holy Roman Empire in 962 by Pope John XII. Otto and his army had come to the aid of John XII, the so-called boy-pope. German had become more than a language; it was now a people and a territory.

This empire was the continuation, some said, of the Roman Empire, which ended in 476. We’re going to scratch the surface of this early history, but note that Charlemagne (Roman emperor from 800-814) had a lot to do with establishing the groundwork for the Holy Roman Empire. His elaborate palace at Aachen, on present-day Germany’s border with Belgium and Holland, established a capital and set the tone for rulers with grand plans for several hundred years. This early history is kind of fun just for the names: Louis the Child, Charles the Simple, Arnulf the Bad, Henry the Fowler.

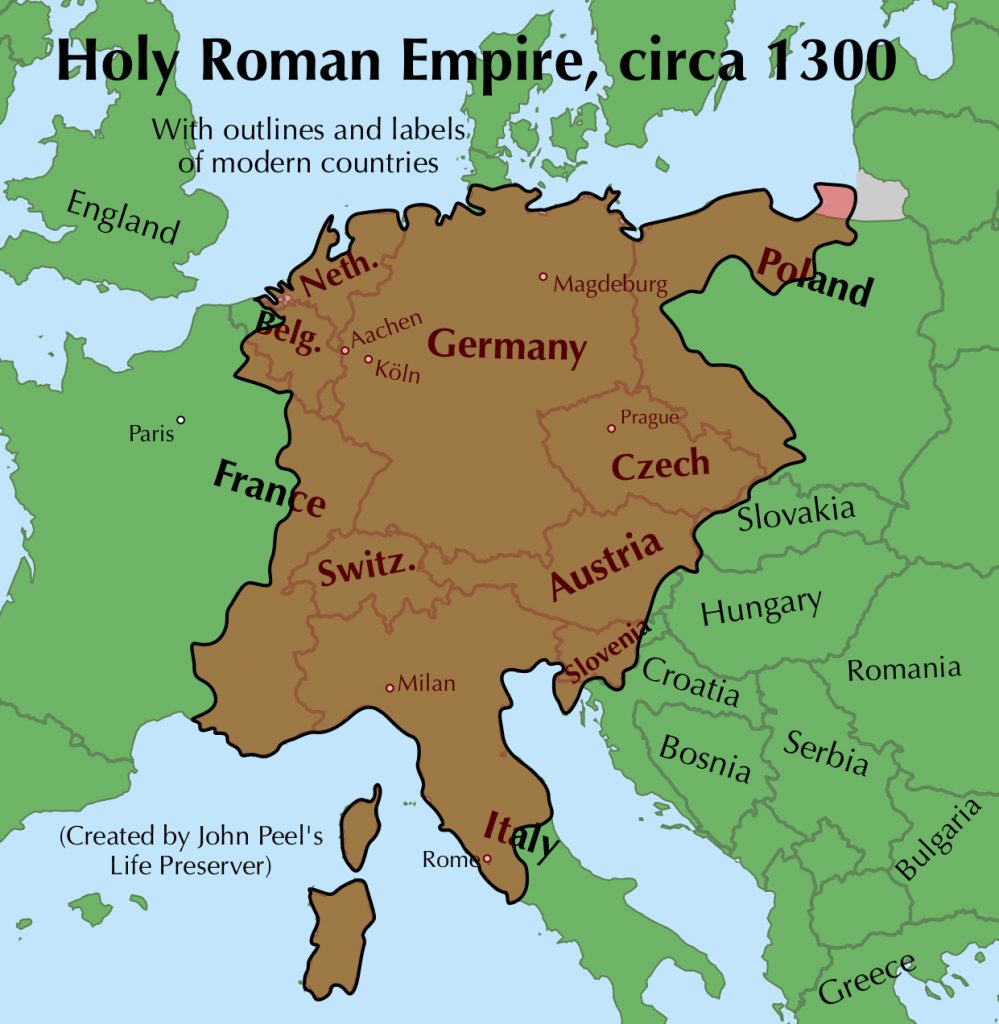

At times, the Holy Roman Empire included present-day Germany, Italy, Switzerland, Austria, Hungary, Czech Republic, Slovakia, parts of Holland, Poland, and France. It reached its greatest extent in the 13th century.

Keep in mind that this was really a loose conglomeration of principalities, fiefdoms, duchies, whatever they were and whatever you want to call them. Various kings, princes, bishops, dukes, nobles, and all sorts of wanna-be landlords often battled among each other to rule various areas. If you swallowed up an extra kingdom or duchy, you might be nice and give one to a brother or half-brother or well-connected cousin.

In 1226 the Teutonic Knights spread east and began their conquest of Prussia, which basically lay along the Baltic, in what we now refer to as Poland and Lithuania. (By 1525 Prussia became the central part of a duchy in the Holy Roman Empire.) Also around the 13th century, England, France, Spain and other areas were becoming solidified, while German areas were not. The solidified areas, with their greater size, gained a major advantage politically and militarily.

The Renaissance did not miss German cities. Scholars evolved. Literacy became commonplace. Capitalism developed. In 1471 a printing shop opened in Nuremberg; it housed two presses and established the city as Europe’s printing capital. (Probably doesn’t need to be said that the Bible was a best-seller back then.)

Then a guy named Luther got things stirred up in 1517 by posting his 95 Theses on Wittenberg church and insisting on worshipping God rather than the Pope. A religious schism grew ever wider.

The Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648)

OK, that’s a lot of years to keep fighting. So how to simplify this. Let’s see. Basically you need to understand that it is often called an “unmitigated disaster” for the German people.

A lot of the war involved battles between Catholic armies and Protestant armies. Generally the Catholics ruled the south (nearer to Rome), Protestants the north.

Everybody who was anybody got involved in the Thirty Years’ War – the French, English, Dutch, Spaniards, Swedes, and Danes. The Germans had the misfortune of being in the middle of all the bloodbaths and pillaging. The Holy Roman Empire was the battleground as all these powers duked it out.

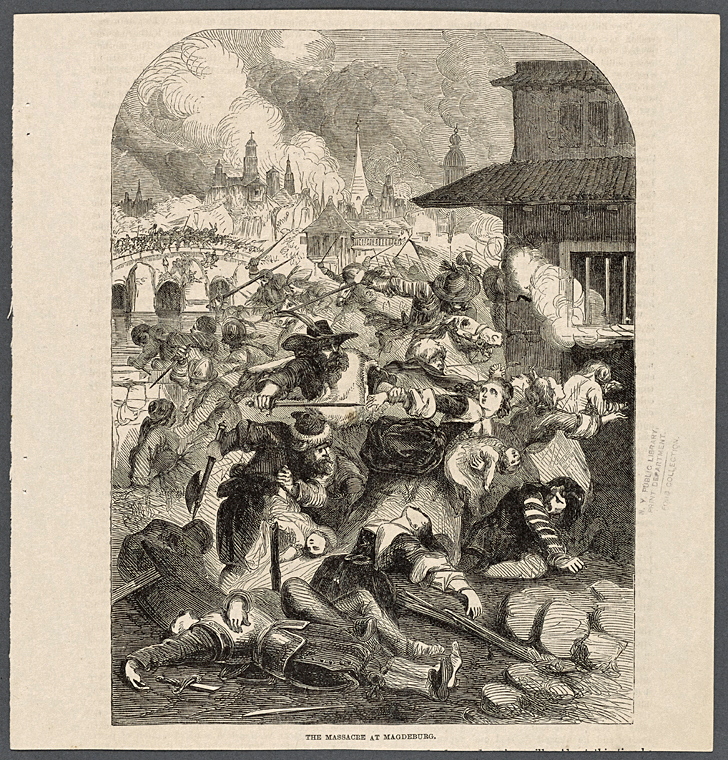

In the end, a lot of people died due to war and pestilence (epidemics) – estimates are between 15 to 30 percent of the Holy Roman Empire’s population. Many were massacred, the most famous incident being the Sack of Magdeburg on May 20, 1631. The Imperial Army and Catholic League massacred about two-thirds of the 30,000 residents of Magdeburg, which then was one of the largest cities in Germany. It’s located in Saxony, northern Germany, about 70 miles west of Berlin. Similar events occurred around the empire. Residents were displaced by marauding soldiers, of whom many were mercenaries from all over Europe.

Perhaps you’ve heard of the Peace of Westphalia. That’s where the treaties ending the Thirty Years’ War were signed (in Münster and Osnabruck). After 1648 the Holy Roman Empire was relegated to pretty much just Germany as we now know it. (With Austria and a couple other dabs of land thrown in.)

For our purposes, the biggest result of the war was the fragmentation of the empire into hundreds of autonomous political entities, most of them very small. By one count: 300 principalities, 50 cities, 2,000 imperial counts and knights. One entity was the Abbey of Baindt in Swabia, a few hundred acres populated by twenty-nine nuns. Power was decentralized.

The good news: The Catholics and Protestants decided they had to coexist because they were really tired of fighting.

Emigrants to the U.S. (1680-1760ish)

The Thirty Years’ War displaced many people, but few went to America until a few decades later. From the 1680s to the 1760s lots of German immigrants began arriving in the New World, particularly in Pennsylvania, upstate New York and Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley. In Germany some had suffered religious persecution, some had trouble taking ownership of farms. They were seeking better economic conditions, religious freedom, the promise of owning land.

Germantown was established in northwest Philadelphia in 1683 by Quaker and Mennonite families from Krefeld, in west-central Germany (North Rhine-Westphalia). Germantown was a focus for German immigrants for decades.

Many U.S. immigrants came from the Palatinate region along the Rhine River in what’s now southwestern Germany, which was devastated first by the Thirty Years’ War, then several other conflicts. Plundering French troops in the last half of the 17th century, then a bad winter in 1708-09 pushed many Palatines to leave. These were known as the “Poor Palatines.”

Between 1727 and 1775 about 65,000 Germans landed in Philadelphia and settled in the region. Most were from southwest Germany – the Palatinate, Rhineland, Württemberg, Baden, and German Switzerland.

1700s and the rise of Prussia

Prussia expanded and became the rather large Kingdom of Prussia in 1701. Later, under Frederick II (the ruthless philosopher king who ruled from 1740-86, also known as Frederick the Great), it began to expand its holdings within the Holy Roman Empire. Prussia, or Brandenburg-Prussia, is in northern Germany, Berlin its center. Joined in battle by Saxony and Bavaria, Brandenburg-Prussia took over Silesia from Austria in the 1740s. Silesia is now part of Poland, with slivers in the Czech Republic and Germany. (Remember, Austria, under the Habsburg monarchy, was still part of the Holy Roman Empire, and was its greatest power.) There’s more, but the main point is that Prussia was flexing its muscle, building its kingdom.

Meanwhile, the many states and principalities within the Holy Roman Empire were doing what they could to establish their own little fiefdoms. Many of them built castles, their own Versailles, which are so nice to look at today but were cursed by the subjects who paid for and built them back in the day.

(I know you’re curious: Why is the name Prussia so similar to Russia? There seems to be no clear consensus. One thought is that it derives from the Slavic “Po-Rus,” which means “the land near the Rusi,” or Russians.)

Early 1800s: The Holy Roman Empire’s end

The American Revolution in the 1770s, the French Revolution in the 1780s. Scary times if you were a monarch. After throwing off their monarchy, and under Napoleon Bonaparte, the French took over Holy Roman lands west of the Rhine in the 1790s. Seeing France’s military might, the Prussians and Austrians did not yet challenge him.

After winning a couple more battles, most notably against Austrian and Russian armies at Austerlitz in Moravia in 1805, Napoleon was in control. As part of peace terms, Napoleon tinkered with the old order in the Holy Roman Empire, dissolving it forever. Bavaria, Wurttemberg, Baden, and Hesse-Darmstadt were given full sovereignty. Prussia decided to battle the French, but in 1806 Napoleon’s forces defeated the Prussians and occupied Berlin. Prussia lost about half its territory under a treaty.

Yet, in trying to promote the expansion of his own empire, Napoleon unwittingly encouraged German nationalism and perhaps paved the path for a unified Germany. This foreign invasion and domination inspired German nationalism. Occupying forces brought reforms that favored people “of property and education,” and gave Germans hope for an improved life. Change was under way.

1815: The German Confederation

Napoleon was defeated in 1814, and leaders from the former Holy Roman Empire had to figure out: what next?

These leaders met at the Congress of Vienna in 1815, and the German Confederation was formed. This association comprised 39 German states, the largest two being Austria and Prussia. Minor kingdoms were Bavaria, Württemberg, Saxony, and Hanover. Smaller duchies included Baden, Nassau, Oldenburg, and Hesse-Darmstadt. It also included the free cities of Hamburg, Bremen, Lübeck, and Frankfurt am Main. Prussia grew, adding the Rhineland and Westphalia as provinces.

The Confederation had little central power. That suited the times but didn’t allow for rapid adaptation as the industrial age, with its factories and railroads, brought huge changes later in the century. Mechanization came to textile mills and coal mines. Banks helped new enterprises, and an upper middle class formed. The population shifted. Farmers’ children left for factory work in cities. Small farmers saddled with financial obligations left for the New World.

The famous potato famine of the 1840s affected more than Ireland. A famine hit Northern Europe too. Change and reformation were in the air, leading to the “Revolutions of 1848” that affected several areas around Europe. In early 1848 came a series of uprisings against various governments of the German Confederation. You had working class radicals, middle class reformers, an aristocracy, all with differing agendas.

These “revolutions” prompted a national assembly and the talk of a new order. But a rift grew between Great German (Grossdeutsch) and Little German (Kleindeutsch) movements. The Grossdeutsch backers wanted Austria (the Habsburgs) to play a key role in a new nation. The Kleindeutsch wanted to shed the Austrian empire, which also included Slavs, Magyars, and Italians – non-German speakers. In the end, however, the German Confederation founded back in 1815 was restored. The aristocracy basically won the day, and many of the reformers and radicals were exiled. Perhaps this included one of your ancestors.

(Historical side note: As these big and radical ideas flourished, Prussian-born Karl Marx’s “Communist Manifesto” was published in 1848. Despite what some of us assumed in our wayward childhoods, he is not one of the Marx Brothers.)

Emigration, 1820-1910

Although Germans had been leaving for America since the mid-1600s, they didn’t start emigrating en masse until around 1816, just after the Holy Roman Empire’s demise. The lure of free, large acreage drew them.

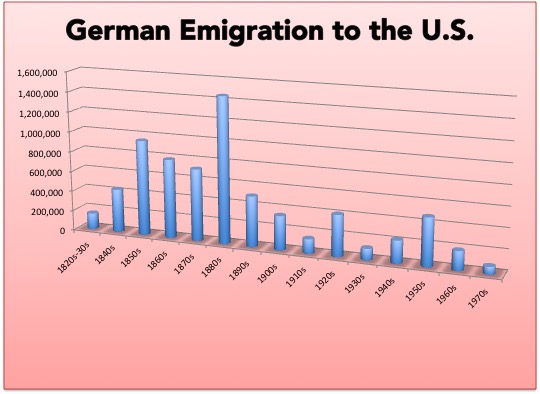

More than 5 million Germans emigrated to the United States from 1820-1910. From 1840 to 1880 Germans comprised the largest group of U.S. immigrants. After the 1848-1849 revolutions, many were political refugees and were referred to as “Forty-Eighters.” Others came due to economic hardship, or to escape the riots and rebellions.

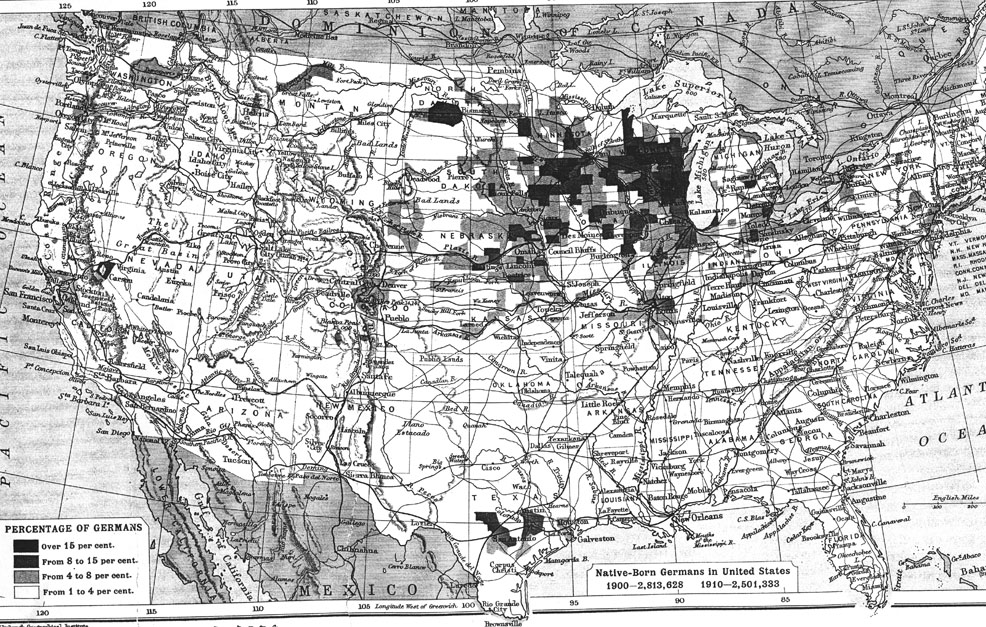

The Midwest, including the Great Lakes states, were popular spots for arriving Germans. Milwaukee (think beer), Cincinnati, St. Louis, Chicago, Cleveland, Omaha. Lots of Germans. Many settled on farms, as well. My great-great-grandfather, John Thurnes (born circa 1830) arrived in America in the 1840s or 1850s. He settled in Chicago. Not sure if he was a Forty-Eighter, but he did brew beer.

Many Forty-Eighters, and their kids, found themselves fighting in the U.S. Civil War. More than 176,000 Union soldiers were born in Germany; the Confederacy had but a fraction of German-born fighters on its side. (To back up a bit, it’s notable that many Germans arrived during the American Revolution to fight on either side. Hessian troops, from the state of Hesse, were hired by the British, and some remained following the war. One Prussian general, von Steuben, is notable for whipping General Washington’s troops into shape.)

Some of you will find that your ancestors arrived in America in coordination with one or several of these events. For some emigrants, undoubtedly these political developments pushed them out of Germany. But others of you may not find any obvious link. Some people left because the draw of opportunity in the New World – the dream of owning large tracts of land, or uniting with family or friends who’d already made the voyage – pulled them in.

1866: Prussian-Austrian split

In 1860-61, under nationalistic fervor, Italy formed. First the Kingdom of Sardinia wrested Lombardy and other lands from Austria. Then northern Italy joined with the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies to unify the country we recognize today.

Could the Germans pull this off too?

In 1862 William I (later Kaiser Wilhelm) named the conservative Otto von Bismarck as prime minister of Prussia. Bismarck was a man on a mission. In 1866 he enlisted Italy’s help in a war against Austria, while many German states sided with Austria. It took Prussia less than two months (thus, The Seven Weeks’ War) to rout Austria (the Habsburgs). The underdog Prussians, using techniques gleaned from the U.S. Civil War, utilized innovations of the Industrial Revolution – railroads and telegraph, improved cannons and rifles – to achieve the upset.

The resulting peace negotiations finally broke up the Prussia-Austria alliance for good. The victorious Prussians annexed several German states and cities, and the German Confederation was dissolved. In its place came the North German Confederation, with Prussia in charge. Meanwhile, several southern German states, including Bavaria, remained independent.

1870-71: Franco-Prussian War, and Germany’s creation

The North German Confederation came out of the Seven Weeks’ War of 1866 strong and fairly united. Still, Bismarck wanted to add the southern German states to the empire. Things came together for Bismarck with the outbreak of war with France in July 1870. (Wars started for really stupid reasons back then, and this one had something to do with the King of Spain and a perceived slight by the French against William I. The truth was that after dominating the Austrians, Bismarck was just itching for a battle with the French.)

For this war, the Franco-Prussian War, the southern German states teamed with the North German Confederation, and they wholly routed the French. Paris fell on January 28, 1871. A few days before that, at Versailles, William I was proclaimed emperor (Kaiser) of a new, united Germany, and a constitution was formed. The southern states of Baden, Hesse-Darmstadt, Württemberg, and Bavaria joined, creating basically the Germany we know today. It included 41 million people – most German-speaking areas other than Switzerland and Austria. At this point Prussia made up three-fifths of the population and three-fifths the land mass of Germany. That, however, would change.

As part of a treaty with France, Germany got 5 billion francs and added the Alsace-Lorraine region along the French-German border. Residents of Alsace-Lorraine were given a few months to decide whether to declare an allegiance to Germany or to leave. Some bolted for America (including perhaps my great-great- and great-grandmothers, although details are a bit sketchy).

Economically, a boom began around 1850 continued until 1873, when a worldwide depression hit. This brought a rash of emigration to both North and South America, particularly in the 1880s. From 1881 to 1890, 1.45 million Germans came to the United States, the highest ever from any decade. My great-grandfather Adam Schatz was among them.

The Great War

If you stayed in Germany, you found work much easier to snag after 1895. From then until 1907, the number of workers in machine building doubled. Emigration saw a rapid decline. Berlin and the Ruhr Valley (the Ruhr flows through west-central Germany and dumps into the Rhine) contained many of the factories. By 1914 Germany was producing twice as much steel as Great Britain. Germany was moving steadfastly urban.

Germany became a naval power (steel helps), and established colonies in Africa and even in the Pacific in its quest to become a dominant world power during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Germany allied itself with the Austro-Hungarian empire. A sense of nationalism grew, and some folks itched for a greater global role, and toasted to “the day.”

We know what comes next. The Austro-Hungarian empire’s heir to the throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, along with his wife, was shot to death in 1914 in Sarajevo. The trigger-puller was Gavrilo Princip, a Bosnian-Serb who was part of an assassination team (members of the radical group Young Bosnia) incensed by Austria’s annexation of Bosnia. That set off what some say was an unavoidable chain of events. Austria wanted military revenge on the tiny nation-state of Serbia, the Russians sided with the Serbs, and the battle was on. France and Great Britain sided with Russia, leaving Germany badly outgunned for the long term. About 2 million German soldiers died during the War to End All Wars, including my great-uncle, Ernst Schatz (1897-1917). Ernst was among those many Germans caught up in the nationalistic fervor of the day, only to discover first-hand the horrors and insanity of war up-close. He was wounded once before returning to battle for his ultimate demise.

As we also know, the war’s outcome for the Germans was not good. The Treaty of Versailles in 1919 restored Alsace-Lorraine to France and took away a good chunk of Prussia to form the newly created country of Poland. (Technically this was the Second Polish Republic.) The Austro-Hungarian empire dissolved. Czechoslovakia declared its separation from the Austro-Hungarian empire in October 1918.

In Germany there was a revolution, the economy tanked, the Spanish Flu killed a bunch of people and wouldn’t let up. Somehow Germany survived, now as the democratically based, so-called Weimar Republic – inspired by the ideals of the 1848 revolution. It was not a good time to be German, and another wave of emigration occurred. This wave included my grandfather, William Maier (1897-1969), who arrived in Boston from Germany in 1923.

The Second World War

What happened next is chronicled in hundreds of thousands of history books and films. The Weimar Republic failed, partly because of the no-win situation regarding the economy. Germans quickly lost faith in it. The Austrian-born Hitler weaseled his way to power and established the Third Reich. (The First Reich was the Holy Roman Empire, the Second Reich was Germany from 1871-1918.) Hitler’s army and potent air force took Czechoslovakia and Poland, and – really, this again? – another world war was under way.

Again in the Second World War Germany was thwarted militarily, and the war’s conclusion produced another mass emigration, many Jews of course, and ultimately a split between West (democratic) and East (communist).

West and East were reunified in 1990, and everyone lived happily ever after and pretty much stayed where they were. Or something like that.

The end

OK, so there you go: An extremely boiled down look at the history of Germany, with a few dates and events that might help you understand your ancestors and perhaps give you some insight into why they left for the New World.

Or it’ll get you more interested and you’ll take it from here, because there’s a ton more to know.

Just keep in mind that maps in the 1840s were different from what they are today. If you really want to understand where your ancestor was from, look at a map of the period.

Good luck in your pursuits.

Sources used:

The Horizon Concise History of Germany, Francis Russell, 1973, American Heritage Publishing Co.

Germany, Britannica Library online.

Europe 101: History and Art for the Traveler, fifth edition, 1996, Rick Steves and Gene Openshaw,

Wikipedia, various sites.

History.com

Holy Roman Empire, Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, sixth edition.

The Historical Society of Pennsylvania online, www.hsp.org