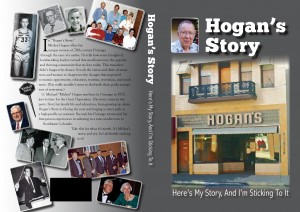

Hogan’s Story:

Here’s My Story, and I’m Sticking to It

(Note: The following is an excerpt from the Preface of “Hogan’s Story”)

For years I resisted writing the complete story, feeling that if I told all the amazing incidents of my lifetime in Durango, I might have to move. So in this writing I limited my purpose not just to providing family and personal history, of which I have included quite a lot, but to focus on telling the story of the positive developments that occurred here between 1940 and the present that have made Durango and La Plata County a place where the wonderful quality of life attracts many new citizens. …

I particularly want to thank the many citizens of La Plata County who allowed and supported all the improvements even when not involved in making them occur. The majority of citizens were supportive of the leaders in their efforts to see each improvement to fruition. The prevailing attitude of the area natives has been to accept newcomers and allow the quality growth that occurred between the years 1940 and 2000.

And finally, I want to apologize in advance for the names of some great citizens I may have omitted and ask forgiveness for having overlooked them. So this is my story, and I am sticking to it!

___________________________________________________________________________________________

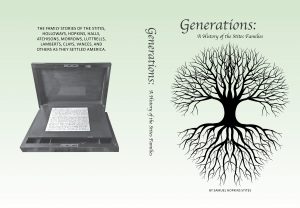

Generations:

A History of the Stites Families

(Note: This is an excerpt from the Introduction to “Generations: A History of the Stites Families”:)

American history is filled with heroic deeds, conflicts, disasters, major achievements.

This biography of the Stites ancestors contains stories of all this, including many twists and surprises. Through these ancestors, through the many family branches that we’ll trace back for hundreds of years to the Old World, you’ll not only see where you came from, but you’ll witness the growth of a new nation. You’ll experience its highlights, its marvelous inventions, its growing pains.

Through these ancestors we’ll come into contact with many important events in U.S. history, including both civil and world wars, social movements (Nashville journalist Libbie Luttrell Morrow campaigned for women’s voting rights in the 1910s), and even aviation (Samuel Stites, a pilot himself, co-hosted aviator Amelia Earhart just before she crossed the Atlantic Ocean).

Many more such nuggets fill the following pages.

Start at the beginning. Or pick a chapter, and dive in. Enjoy this exciting, ever-evolving family history.

_________________________________________________________________________________________

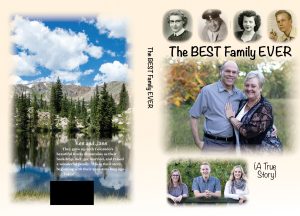

The Best Family Ever (A True Story)

(Note: This is an excerpt from the Introduction to “The Best Family Ever (A True Story)”:

This is the story of an understated engineer and a bubbly public relations mogul – their ancestry, their lives, and their offspring.

It begins with family histories filled with both triumph and tragedy. This ancestry includes tough women (check out Dicy Holman of Tennessee in the Thurber chapter). It includes bank robbers and worse (same chapter).

It includes German, Czech, and Swiss immigrants who saw America as the promised land, bravely uprooted their lives in the Old World, and made their dreams come true in the New World.

Just as John F. Kennedy was elected and began his short reign as president, Ken Dvorak and Jane Thurber were born in the Denver area. Fortunately, Ken and Jane mostly picked up the good characteristics of their gene pool. Their relationship began with a bonfire, and the flame lit in 1977 still burns brightly today.

Their three talented children – Kyla, Bridget, and Dan – continue to be their pride and joy.

So sit back and enjoy as you thumb through these pages. Be prepared to learn a little about U.S. and world history, the Mexican restaurant business, nuclear engineering, and giving speeches to thousands of onlookers while keeping nerves of steel. And that’s just a tease.

Read on!

_________________________________________________________________________________________

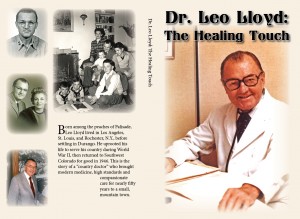

Dr. Leo Lloyd: The Healing Touch

(Note: This is an excerpt from “Dr. Leo Lloyd: The Healing Touch”:)

Having no place to live upon arrival in Durango, Leo and Mary took a room at the Strater Hotel on Main Avenue at Seventh Street. It was Room 222, to be exact, and it was directly above a pharmacy.

Here’s the curiosity: Almost exactly thirty years later, author Louis L’Amour would bring his family to Durango and they’d stay in Room 222, which by 1966 was above a bar with a ragtime piano. L’Amour would type parts of many Westerns of his famous Sackett series there for a month every summer.

Even though the Depression was still in full swing, the town was busy. The smelter just south of downtown was working and there was a lot of activity. Around late November 1936, Leo and Mary finally found a small second-floor apartment to rent at 1020 East Third Avenue; they stayed there for “quite some time.” And Dr. Lloyd settled into his new task of operating a hospital. This didn’t prove a simple task.

“I’m sure if I had to do this all over again, I would do it without buying a hospital,” he said. “It simply is too much to practice and operate all of the things that go into running a hospital, such as food, cleaning, and so forth.”

He and Dr. Martin got along well, and Leo learned from assisting Dr. Martin in surgery. “I was completely unfamiliar with surgery,” Dr. Lloyd said, “never having even sewed up a cut when I was in Rochester.”

The two new doctors got along well, but their attitudes and goals didn’t mesh with their short-time partner.

“Dr. Ochsner was a different type of man,” Leo said. “He was well-trained for his time, but his attitude toward his patients was totally foreign to ours.”

For one, Ochsner insisted upon being paid before an operation. Anything during surgery that was beyond normal – breaking up adhesions, or removing an ovary, or whatever – would get an added charge. Ochsner would exit the operating room and ask for a check for the extra work.

“This affair was a cash business with him, and we really didn’t exactly know how much money he was collecting,” Leo said. “In many ways we were very happy when our time came to disassociate ourselves from him.”

Ochsner performed abortions, which Leo, as a Catholic, could not condone. Martin was against it too. Half the hospital’s patients were recovering from abortions, Dr. Lloyd said in an interview with Barbara Moorehead. “It was an open secret Ochsner would do a procedure on anyone with the cash on hand. Women came all the way from Albuquerque and Las Vegas.”

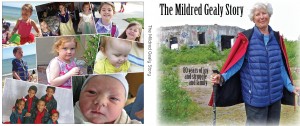

The Mildred Gealy Story

(Note: This is an excerpt from the beginning of “The Mildred Gealy Story”:)

She was raised in an isolated, rural town, yet grew up to see and explore the world.

When her first husband died tragically, she forged ahead on her own. When cancer claimed her second husband, she again bounced right back.

For her 70th birthday she got a tattoo.

If the woman born Mildred Gealy has learned anything in this life, it’s how to adapt, how to be resilient under duress. It’s something she’s had to do, and it’s what she’s learned to embrace. That was the only way.

“It’s amazing what you can go through and survive,” says Millie, who bore four children, is mother to eleven counting step-kids, and grandmother to at least 31.

Since she left tiny Gordon, a small town in the Sandhills of Nebraska, for college in the early 1950s, she has taken on life’s changes and curveballs and hard knocks with grit and style. With a firm and gentle hand, she has passed on those hard-earned lessons to succeeding generations.

You celebrate the good times, and persevere through the hard times. She’s had a lot of both.

To better understand Mildred Gealy Genge Esten Radke, it’s probably best to start by going back in time.

Family history

They arrived from Pennsylvania, with deeper roots in Scotland. They arrived from Massachusetts and Iowa, from family trees traceable to 18th-century North Carolina and Scotland again. Mildred’s great-great-great-grandfather, James Immigrant Gealy, emigrated to Pennsylvania from northern Ireland in the mid-1700s, before there were any “united” states.

Wherever they came from, they eventually ended up in Sheridan County, in northwestern Nebraska, to create the chain of events that ultimately gave birth to Mildred Gealy.

Give some credit to Abraham Lincoln and the Homestead Act. …

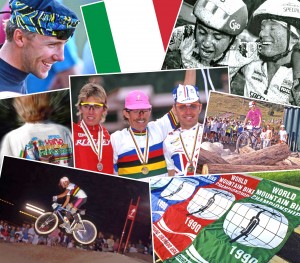

How Durango snagged the 1990 Worlds

(Note: This was a project done for the Iron Horse Bicycle Committee and the 25th anniversary celebration of the 1990 World Mountain Bike Championships. To order the book online, click here.)

When Ed Zink and the Iron Horse Bicycle Committee got a call about Durango possibly hosting the 1990 World Mountain Bike Championships, the response was easy and quick.

“I said, ‘No thanks, we don’t want to bid.’ And I hung up,” Zink recalls.

They’d just finished running the 1989 Iron Horse and didn’t want to contemplate the immensity of organizing and hosting a world-class event.

“The first two calls I said ‘no thank you. We’re busy, we’re tired,’” he says 26 years later.

The story behind the scenes, the political intrigue, the community’s gallant efforts – well, OK, it’s not Hollywood movie stuff. But it is pretty fascinating. Our city had to write the script on hosting an off-road world championship. It had to arrange venues, build courses, raise money to meet a $500,000 budget and enlist the help of hundreds of volunteers. And this all had to be done in a year – far, far less preparation time than typical for a similar sized event.

Those involved in preparation will tell you two things: One, it was a ton of work that increased exponentially as the Sept. 11-16 races neared. Two, it was a life-changing event – in a good way.

A photo collage of 1990 Worlds still hangs on the wall of Dan Noonan’s office in Bodo Industrial Park. Noonan, the retiring chief of Durango Fire Protection District, was chief of Hermosa Cliff Fire 25 years ago. He recalls “everyone rowing in the same direction” to keep riders and spectators safe.

“This event and its successful memories resides not only in my office but in my heart,” he says.

Before proceeding with the story of how Durango changed its mind and then prepared for the onslaught of thousands of visitors from around the world, some background is in order.

Semi-organized mountain bike races hadn’t begun until the late 1970s, so no one had decades of experience in putting on big events. The Iron Horse added mountain biking in 1984, and Durango hosted the National Off-Road Bicycle Association (NORBA) nationals in 1986 and ’87.

“World” championships had been held since 1986, but not by a body recognized on a world scale. So the United States and Europe each held a “world” event. To riders such as Ned Overend, this was maddening.

“It was confusing, and it wasn’t official,” says Overend. He constantly had to explain to befuddled listeners that he was the European world champion. Or the U.S. world champion. The Union Cycliste Internationale was cycling’s recognized world-governing body.

“It really needs to be recognized by the UCI to have a unified world champion,” he realized.

And in 1989, indeed, the UCI agreed to sanction off-road worlds and to have the sport’s birthplace, the U.S., host it.

At that point the U.S. Cycling Federation (now known as USA Cycling) took charge of picking the host site. California’s Mammoth Mountain ski resort and New York state’s Lake Placid planned to bid, but UCI’s policy was to have three bidders, Zink recalls, so the USCF and the other two sites urged Durango to bid.

On the third call, Zink relented. “OK, we’ll fill out the application.”

Of course, you might as well play to win. “As soon as we got into it we’re like, ‘We’re going to win this sucker,’” Zink says.

Among the questions on the obviously European-influenced application: Where is the nearest train station?

“We just answered it,” he says, laughing that they didn’t explain the tourist-oriented Durango & Silverton Narrow Gauge railroad connected nowhere useful for transportation purposes.

On their tour of the bidding sites, USCF officials were heading to Durango from Mammoth – not a quick link. To shorten their travel time by nearly a day, Durango organizers chartered a plane for the officials. If that didn’t impress, then perhaps having nearly 100 of the town’s political and business leaders greet them at the Red Lion Inn (now the DoubleTree) did.

“It was the whole town there to say we could do this,” Zink says. “The community’s enthusiasm is what made the impression.”

One of the major financial backers was Don Mapel, who not only is a mountain biker but, perhaps fortuitously, owns the Durango Coca-Cola distribution plant.

“I thought from a marketing standpoint, not only for my company but for Durango itself, this was going to give us some real exposure that is long-lasting,” Mapel says. “I think that proved to be correct.”

With the USCF’s recommendation, at a meeting Sept. 28, 1989, in Brussels, the UCI officially granted the first-ever Worlds to Durango, which beat out Mammoth and Park City, Utah. (Apparently Lake Placid withdrew or did not make its bid.)

“The outstanding support of not only the Durango community, but that of the entire state of Colorado has been overwhelming and was certainly a significant factor in our determination,” the USCF wrote in a congratulatory letter to Zink on Sept. 29, 1989.

The Durango organizers’ first fear was that it wouldn’t get the Worlds. The second fear was that it would. Now, the work began.

An organizing committee officially formed and got busy. Eric Backer, appointed director of registration and results, recalls that Worlds was “pretty much all I did for a year.”

One thing that quickly became apparent is that the Durangoans were incapable of answering many crucial questions that cropped up, such as, “How many riders can our country bring?” Or, “How many feet should the downhill course drop?” So Zink, Backer, and NORBA director Dean Crandall flew to Paris for three days of meetings with the UCI’s Mountain Bike Technical Commission.

Backer says his role was to make sure they didn’t get lost in the Parisian subway system. And, along with Zink, he wore cowboy boots. “Just two hicks in the City of Light,” he jokes.

Zink says the Europeans ate up the cowboy image. “We made a point of being Western. We did several things that were very cowboy, and the point was it would get their attention.”

After sitting in a hallway where they were offered warm beer, they were eventually ushered in. Zink says the Durango organizers insisted on having a rulebook, and basically overnight, he and Patrice Drouin, a UCI official from Quebec who was familiar with mountain bike racing, wrote the international rulebook for UCI.

Notes from the three days of meetings, stored at Fort Lewis College’s Center of Southwest Studies, reveal a couple things. One is that some UCI officials can be rather territorial and pompous. Another is that on Sunday, April 22, 1990, the final day, the commission passed “Regulations for Mountain Bike Races.”

“They didn’t read it,” Zink says. “They didn’t know anything about mountain biking.”

Now, the Durango organizers at least had some guidelines. But a lot of work lay ahead, more work than any of them would have cared to believe …

To read more John Peel – Life Preserver stories about the 1990 Worlds, visit Todd & Ned’s Durango Dirt Fondo website.

The following are pieces of human-interest columns that John Peel wrote during his days at the Durango Herald:

Durangoans mourn closing of Hogan’s store

Down in the basement, past the 1920s-era steam furnace, into the room with the piles of once-fashionable plaid pants and bell-bottom jeans, stacks of cardboard boxes line the north wall.

The boxes are labeled in large handwriting. They contain decades-old records, mostly canceled check stubs. One box is from 1946-1955. Nearby are more ancient archives: a 1933 store ledger for the then-fledgling clothing shop, meticulously kept by Georgie Hogan, mother of the current owner, Mickey Hogan.

“I’ve got better than that,” Jerry Poer says.

The longtime Hogan’s Store manager takes a minute to shuffle through a series of drawers in a wooden dresser and finds it: an oversized checkbook from Smelter National Bank. Peruse the checks briefly, and you step even further into the past. The year for the check date has been partly preprinted. It reads 189_.

Yep, there’s some history here.

Here’s the link to the full story: DurangoHerald.com

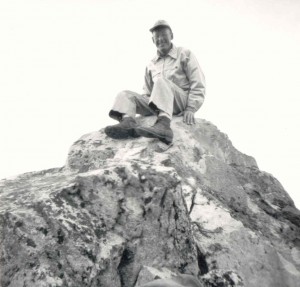

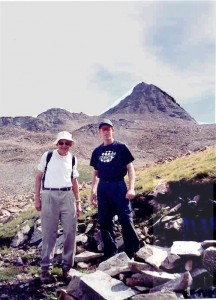

A farewell to my mountain-loving father

(This is the eulogy John Peel delivered at his father Donald Peel’s memorial service Wednesday in Golden. Donald Peel died April 5.)

I wonder if my dad would be embarrassed by all the people here today.

I’m not embarrassed, but I am nervous. I’m a writer, not a speaker. My writing skills, for what they’re worth, come mostly from my mother. My dad influenced my life in many other ways, and I guess his gift I’ll treasure most is a love for the mountains. A love of climbing, a love of walking in the outdoors, of seeing columbine and marmots on high-mountain slopes, of taking those last celebratory steps to the summit.

He was on my first Fourteener, Aug. 31, 1969 – at least that’s the date he wrote in his immaculate records. I was 8 when we climbed Grays Peak that day, he for the ninth time. I’m sure there were times when I wanted to know how much farther it was, or complained I was getting tired. He coaxed me to the top, but not in a demanding way. He never threatened or berated me. I did things right because I didn’t want to let him down.

I know I am a fortunate son. I never had to worry once about whether my father loved or cared for me. I think he attended every one of my little league basketball games for four years straight. He kept coming when our team went a whole season without winning, even – and I’m not making this up – after we lost 73-6. I think he was proud that I scored two of our six points.

When I went away to college in 1979, he started writing a letter a week. He did this for my sister, too. He was no Hemingway, but it was his way of letting us know he was thinking about us. I never moved back to Denver, so he kept writing those letters. Twenty-five-plus years, one letter a week. That’s 1,326 letters.

I remember him being generous, helping out family and friends and acquaintances almost to a fault. He’d give you the shirt off his back, then apologize if it didn’t fit you.

He had a strange sense of humor that confused me somewhat as a child. And he had these quirky sayings I heard over and over.

- “I’ve told you a million times not to exaggerate.”

- When you were driving, it was: “Back up until you hear the sound of breaking glass.”

- When you passed an antique store: “Antiques made while you wait.”

- And perhaps my favorite: “I’ve told you a million times not to exaggerate.”

Ten years ago, he came to visit in Durango. He was 73, but he could still rough it. We drove north of Creede and camped in a tent at 10,000 feet, got up the next day and hiked the long approach toward San Luis Peak, the rare Fourteener he’d climbed only once before. A few hundred feet from the top, he bogged down; he told me to go on to the top, and he’d wait on the ridge. I asked if I could take his pack, lift his burden so he could bag this peak. He could be stubborn in refusing help, but this time he relented. Probably he knew I didn’t want to leave him. In 20 minutes we did reach the summit, and I know he was a happy man. He’d climbed a Fourteener 139 times now, but for the rest of his life, at least when I was around, this was the one he always talked about.

Two weeks ago, he fell and broke his hip. He struggled after surgery to get well, but I guess we all finally come to that mountain we just can’t climb, and my dad had come to his.

I plan to scale a few more peaks as I venture along the trails my life takes me. I’ll always take him with me.

Thanks, Dad.

(This story originally appeared in the April 15, 2005, Durango Herald.)

91-year-old a role model? Not if you ask her

Eileen Albrecht’s friends think the world of her. But they have trouble coming up with the right word to describe her.

They try “solid” or “involved.” But what does that mean?

“Well-grounded” and “unpretentious” are a little better, but they’re hardly terms of endearment. It’s apparent that “flashy” and “flamboyant” are not going to be on the list of descriptors – she’s no attention-seeker.

“Kind” and “gracious.” Now we’re getting somewhere.

The word they don’t use, but seems to fit more than any, is “respect.”

She’s also consistent. Eileen Albrecht, who will turn 91 on May 28, grew up just north of Hermosa and has lived here nearly all her life. Every Monday and Friday, she takes the bus to the Durango Community Recreation Center for an aquafit class with instructor Maureen Keilty. She’s been doing that since the rec center opened 12 years ago and, apparently, hasn’t slowed down.

“I haven’t seen it,” Keilty says. “She knows how to make it work for her.”

Here’s the link to the full story: DurangoHerald.com

An illustrative past

Eddie Martinez is fascinated with Mesoamerican culture – the Chacoans, the Aztecs, the Mayans.

He can talk to you about it, he can write about it and he can definitely draw it.

But what he really wants to do is teach. He wants people, particularly his fellow Latinos, to know about their ancestors’ role in pre-Columbian America. After a career in the entertainment biz, including work as an illustrator for Walt Disney, he also knows how tricky that is.

“If I say I’m going to talk history, everybody goes to sleep. But if I say I’m going to talk about ‘Raiders of the Lost Ark,’ then they go, ‘Ooh, I wanna hear about it.’”

So the Los Angeles native, who now lives in the hills outside Bayfield, is excited about the task he has created for himself. He’s eager to finish his illustrated historical novel. And he’s jazzed about the possibility, however slight, that his book Search for Don Juan and Aztlán, three-plus decades in the making, could become something big.